Overview

- EWG’s new update to its Conservation Database compiles 2017–2020 payment data for five of the largest Agriculture Department conservation programs.

- Only a small proportion of payments from two of the largest programs went to practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from farming.

- Some of the practices that received the most funding actually increase emissions.

Farmers received almost $7.4 billion in payments from two of the largest federal agricultural conservation programs between 2017 and 2020, but only a small proportion of these payments went to practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from farming.

This finding comes from EWG’s newest update to its Conservation Database, which provides 2017–2020 payment data for five of the largest Agriculture Department farm conservation programs.

Through these five programs, the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS, and Farm Service Agency provide payments to farmers who implement voluntary agricultural conservation practices on their land.

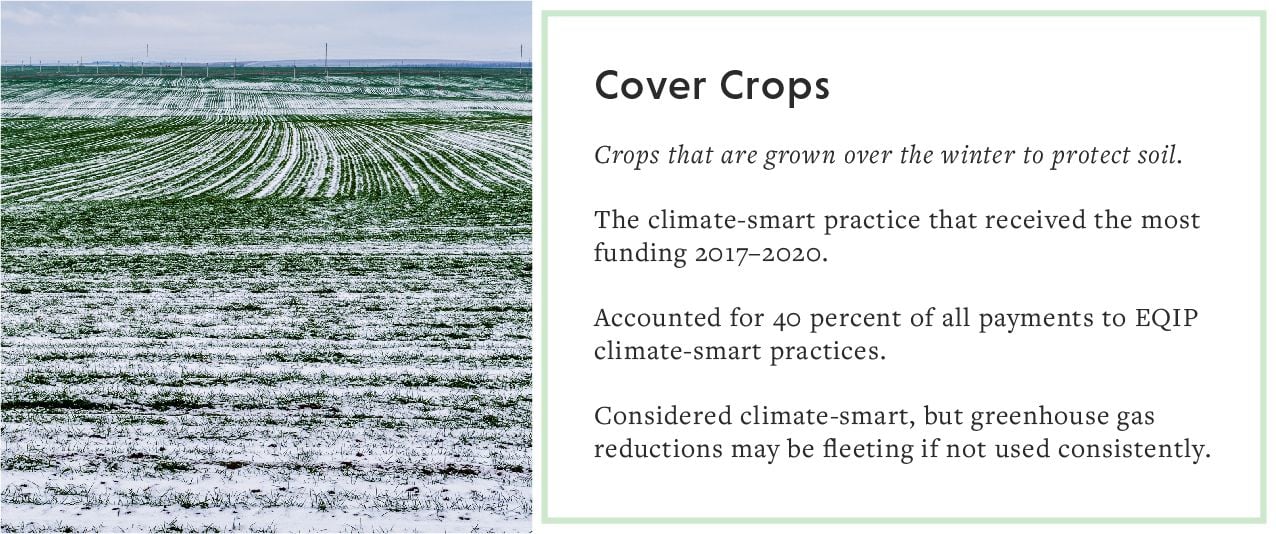

Three of the programs are focused on permanent or temporary land retirement. The other two programs, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, and the Conservation Stewardship Program, or CSP, pay farmers to implement one or more of hundreds of widely varying practices, such as planting cover crops or establishing wildlife habitat. Each practice is assigned a score by the NRCS for how it affects natural resources like water and soil quality.

Very little of the funding from either EQIP or CSP went to the practices the USDA considers climate-smart. Some of the practices that received the most funding actually exacerbate the climate crisis.

In recent years, the NRCS has also designated some of these practices “climate-smart.” Yet our analysis shows that, despite repeated reassurances from USDA leadership that tackling the climate crisis is an agency priority, climate-focused programs and practices are neither prioritized nor well-funded.

In fact, very little of the funding from either EQIP or CSP went to the practices the USDA considers climate-smart. Even more troubling, some of the practices that received the most funding actually exacerbate the climate crisis.

Climate-smart practices got very little funding

EWG’s Conservation Database includes national-, state- and county-level payments for the three biggest conservation programs: EQIP, CSP and the Conservation Reserve Program, or CRP.

It also includes national- and state-level payments for two conservation easement programs, the current Agricultural Conservation Easement Program and the former Wetlands Reserve Program.

This report focuses on EQIP and CSP, the two largest NRCS conservation programs that account for much of federal agricultural conservation spending. (More information about the other three programs can be found in EWG’s Conservation Database.)

Only 23 percent of EQIP payments were for practices that mitigate climate change.

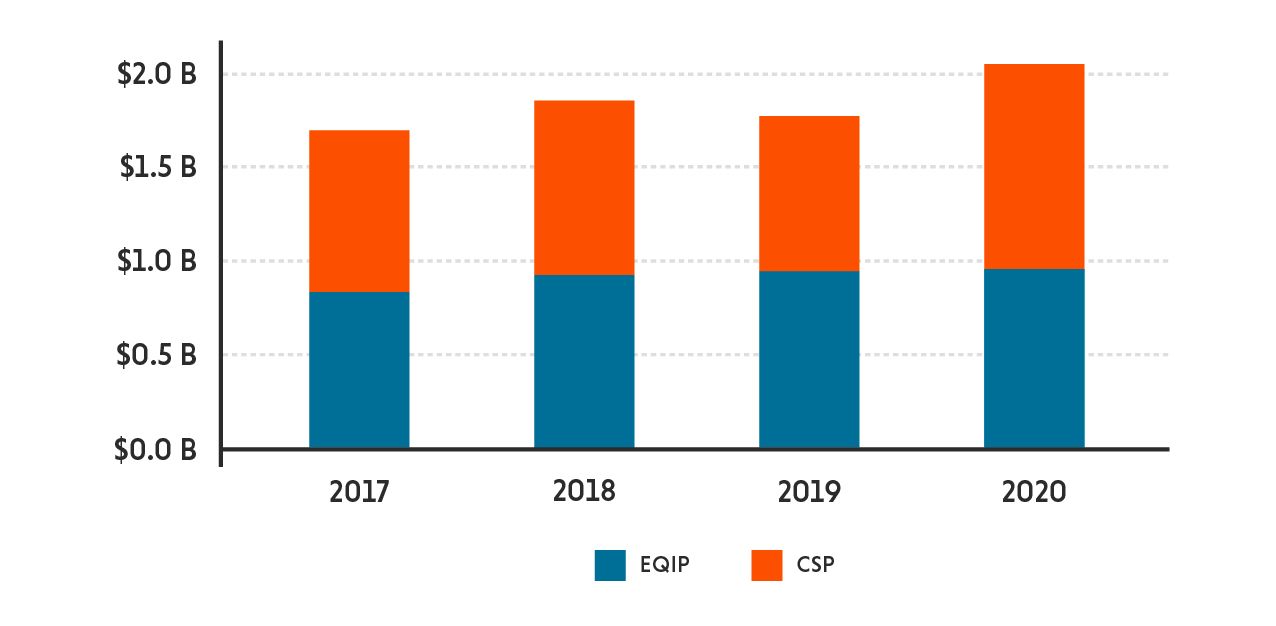

Between 2017 and 2020, total EQIP payments to farmers totaled more than $3.6 billion, and they increased slightly over the period. Yet only 23 percent of payments, or $843.85 million, were for practices that mitigate climate change, according to the NRCS’ list of climate-smart practices and enhancements. This proportion stayed fairly consistent over the four-year period, with climate-smart practices making up 22 percent of total EQIP payments in 2017 and 2018 and 24 percent in 2019 and 2020.

Just one practice, cover crops, accounted for 40 percent of all EQIP climate-smart payments. The other 29 climate-smart practices made up 60 percent of payments. In other words, the USDA relies heavily on cover crops as its main tool in EQIP to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from farming. But research has shown that the climate benefits of cover crops can be fleeting unless they are used consistently and the soil is not tilled after they are grown.

An even smaller fraction of total CSP payments went to NRCS climate-smart practices and enhancements. Total CSP payments between 2017 and 2020 were just over $3.7 billion, increasing by 27 percent over the period – a larger percentage increase than EQIP payments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. EQIP and CSP payments together were almost $7.4 billion between 2017 and 2020.

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

Only 0.3 percent, or $11.4 million, of CSP funding went to NRCS-designated climate-smart practices and enhancements – at least partly because the climate-smart enhancements were not created and funded until 2020. The “climate-smart” designation was applied to practices that already existed in the USDA conservation system at some point, but climate-smart enhancements did not exist before 2020.

Only 0.3 percent of CSP funding went to climate-smart practices and enhancements.

Another reason the spending might be artificially low is the EQIP climate-smart practice list does not precisely match the CSP climate-smart enhancement list. For example, the CSP enhancement code E345106Z stands for the enhancement “reduced tillage to increase soil health and soil organic matter content.” This is not on the list of CSP climate-smart enhancements. But the EQIP code 345 is included within this CSP enhancement code, and in EQIP, this code stands for the practice “residue and tillage management, reduced till” – which is on the climate-smart EQIP practice list.

To rectify this inconsistency, EWG evaluated how much spending went to CSP enhancements that are not on the CSP climate-smart enhancement list but whose codes contain EQIP climate-smart practice codes.

Even with this recalculation – with all CSP enhancements that contain an EQIP climate-smart practice code included – only 5 percent, or $194.75 million, of CSP funding went to climate-smart practices.

What EQIP money funded

A considerable amount of EQIP spending went to practices that pay for structures, equipment or facilities – not what most people would consider agricultural conservation practices.

The 10 most-funded EQIP practices paid out over $1.7 billion – 48 percent of all payments between 2017 and 2020. Of these, seven practices related to structures, equipment or facilities received 30 percent of all payments (Table 1).

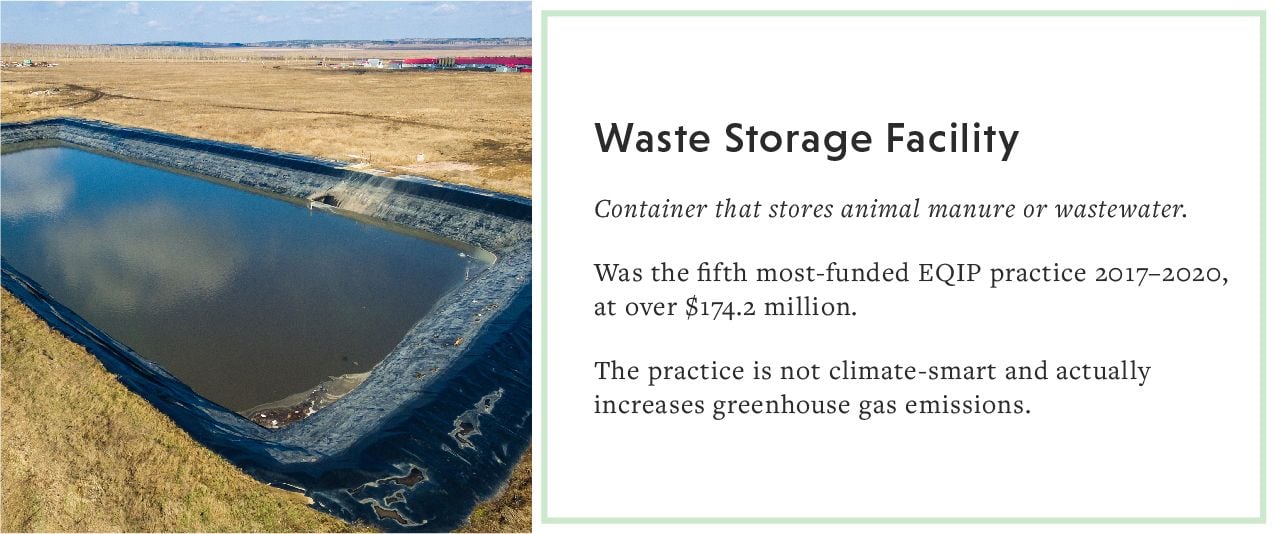

“Waste storage facility” was the fifth most-funded practice, with over $174.2 million going to build such facilities. Not only is this practice not climate-smart but it also increases greenhouse gas emissions, according to the USDA’s own calculations.

Other heavily funded EQIP practices undermine efforts to mitigate climate change. For example, many of the other top 10 most-funded EQIP practices were related to irrigation infrastructure. More irrigation can make water shortages worse, since the climate crisis has increased drought conditions in many parts of the country. The USDA maintains that EQIP projects do not increase water withdrawals, but questions remain.

Table 1. Seven of the top 10 EQIP practices with the most funding were for structures, equipment or facilities.

|

EQIP practice name |

2017-2020 Payments |

On NRCS climate smart list? |

|

Cover Crop |

341,316,524 |

Y |

|

Sprinkler System |

216,551,811 |

N |

|

Fence |

211,866,775 |

N |

|

Brush Management |

209,283,502 |

N |

|

Waste Storage Facility |

174,204,506 |

N |

|

Irrigation Pipeline |

163,052,611 |

N |

|

Irrigation System- Microirrigation |

119,646,285 |

N |

|

Roofs and Covers |

116,451,835 |

N |

|

Livestock Pipeline |

107,599,300 |

N |

|

Forest Stand Improvement |

99,330,495 |

N |

Source: EWG, from public records requests of USDA-NRCS Environmental Quality Incentives Program data.

Six EQIP practices that actually increase greenhouse gas emissions, according to the USDA’s own reckoning, received funding between 2017 and 2020. Besides “waste storage facility,” five of these practices were responsible for over $11.2 million sent to farmers: “deep tillage,” “waste treatment lagoon,” “land clearing,” “precision land forming” and “denitrifying bioreactor.”

What CSP funded

There is a major data transparency issue with how the USDA reports CSP funding. In the agency's responses to EWG’s Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, requests, it sorted the majority of CSP payments by land use – not by practice or enhancement.

In all, 90 percent of all CSP payments were made for annual payments categorized by land use like cropland or pasture, so we cannot know exactly which practices and enhancements most of this taxpayer money went to.

Because of this missing information, the top 10 listed enhancements made up just 6 percent of all CSP payments. The top two enhancements were “reduce risk of pesticides in surface water by utilizing precision pesticide application techniques” and “reduce risks of nutrient losses to surface water by utilizing precision ag technologies.”

The USDA has a data transparency problem

EWG researchers spent almost a year trying to get accurate county-level conservation data from the USDA. This is public, taxpayer-owned data that, by federal law, every person in this country has the right to obtain and review. It should be simple and straightforward for the USDA to pull and share this data with anyone who asks. And we’ve requested, and received, conservation data for many years. (We released our first Conservation Database in 2016, with data going back to the 1990s.)

But starting in July 2021, we were forced to file multiple FOIA requests, exchange many emails with USDA employees and spend countless hours parsing the data we were able to wrest from the agency – only to repeatedly find the data we were given was incomplete, did not fulfill the request or was simply not correct.

USDA’s data gap makes it impossible to form an accurate picture of which practices taxpayer money is being spent on at a county level.

We finally got the correct data, in the correct format, in June 2022 – almost a full year since we filed the original request. (According to NASA, it takes just 7 months to get to Mars.)

Incredibly, this final response was still missing data. Our public records request asked for payments at a practice level in each county for EQIP and CSP. The USDA sent us most of this data – except for practices where there were five or fewer contracts funded in a county in a particular year.

This data gap makes it impossible to form an accurate picture of which practices taxpayer money is being spent on at a county level.

Missing conservation data shows misaligned USDA priorities

By looking at what’s missing, we can clearly see that the NRCS’ climate-smart practices and enhancements are not often funded or adopted.

In the 2017–2020 county-level data, 26 NRCS-designated climate-smart EQIP practices received funding. The other seven climate-smart practices did not have more than five contracts in any county in any given year: “alley cropping”; “anaerobic digester”; “herbaceous wind barriers”; “land reclamation, abandoned mined land”; “land reclamation, currently mined land”; “land reclamation, landslide treatment”; and “stripcropping.”

More than half of the climate-smart CSP practice and enhancement list was implemented on fewer than six properties in any county in any given year.

The numbers were even worse for CSP. Out of the 114 NRCS-designated climate-smart CSP practices and enhancements, only 51 were visible in the county-level data we received – so 63 were missing.

That is, more than half of the climate-smart CSP list was implemented on fewer than six properties in any county in any given year. These include things like “enhance a grassed waterway” and “soil health improvements on pasture” – enhancements that are very likely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Reforms are needed for these programs to sizably reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Congress must reform EQIP and CSP to make efforts to reduce emissions a top priority – and must prohibit spending on practices that increase rather than decrease emissions. Lawmakers must also increase farmers’ portions of EQIP cost-share for structural practices, link CSP eligibility to climate stewardship and focus CSP spending on enhancements for greenhouse gas reductions.

Methane has an outsized impact on the climate crisis, and agriculture is a major source of methane. EQIP and CSP should increase funding for practices and enhancements that reduce methane emissions.

Finally, Congress must make both programs more transparent. Unless legislators quickly address the needless delays and failures in USDA reporting on conservation spending, they will have no way to know whether new spending is flowing to practices and enhancements that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.