As far back as the 1960s, animal studies showed the chemicals caused harm even months after exposure ended and industry studies showed they could migrate from paper and paperboard food packaging into food.

By the 1980s, studies showed PFAS chemicals could pose health risks under a range of circumstances, but the agency continued to approve expanded uses of the chemicals, in addition to new types of PFAS. Here is a timeline of the memos, studies, and other documents detailing at a minimum what the FDA knew about PFAS toxicity and migration into food.

December 23, 1965

FDA allows use of a type of PFAS, chromium complex of perfluoro-octane sulfonyl glycine, for use on paper and paperboard food packaging. The agency says it “is not reasonably expected to migrate.”

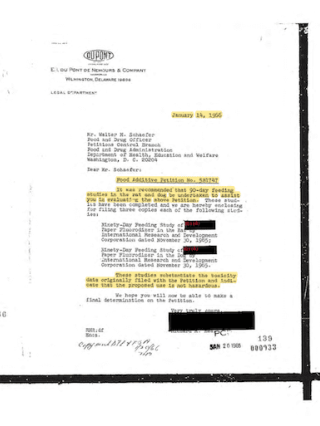

January 14, 1966

DuPont submits two studies to FDA on its PFAS Zonyl RP at FDA’s request. Both 90-day studies showed effects on liver weights, and the rat study showed kidney weight impacts, even months after the chemical exposure ended.

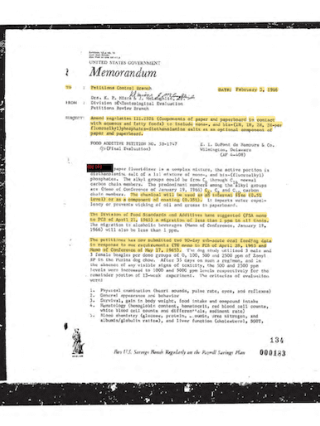

February 3, 1966

DuPont had estimated that 1,000,000 ppt of Zonyl RP could migrate from packaging into food. FDA calculates that the maximum safe level for Zonyl RP to migrate into food would likely be 100,000 ppt.

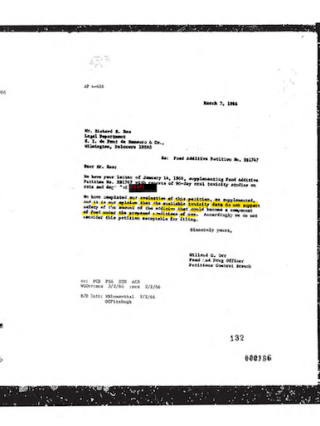

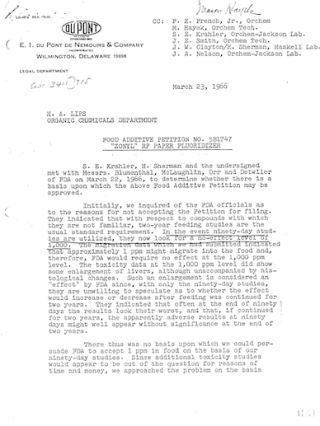

March 23, 1966

In response to FDA rejection, DuPont decides to create new migration estimates, because “additional toxicity studies would . . . be out of the question for reasons of time and money.”

June 21, 1966

DuPont submits new migration estimate to FDA of 200,000 ppt to water at 150 degrees F and no migration to water at 70 degrees F or for fatty food by applying less Zonyl RP to paper and changing its test method.

July 20-21, 1966

FDA determines Zonyl RP is safe at migration levels of 200,000 ppt but requests additional information from DuPont to confirm migration data.

September 27, 1968

FDA approves a 3M petition to use a type of PFAS, ammonium bis(N-ethyl -2-perfluoroalkylsulfonamido ethyl) phosphates, in food packaging.

August 4, 1969

FDA evaluates a 3M petition to expand uses of its approved PFAS in food packaging and finds the additional uses would increase the amount in the daily diet by 25 percent. FDA recommends approving the petition.

August 28, 1970

FDA permits 3M petition to expand PFAS uses in food packaging to include fried foods, bakery products, and hot dry fatty foods. FDA estimates that as much as 2,200,000 ppt of 3M’s PFAS could migrate to food that is more liquid and 4,400,000 ppt could migrate to fatty foods.

October 6, 1970

FDA evaluates a DuPont request to expand uses for Zonyl RP and finds migration could be as high as 510,000 ppt for foods more similar to liquid.

December 8, 1971

After rejecting DuPont’s petition to expand uses of Zonyl RP at the end of 1970, FDA evaluates the company’s resubmitted migration tests for Zonyl RP and recalculates maximum migration as 70,000 ppt for fatty food and 90,000 ppt for liquid food. FDA concludes expanded uses are safe.

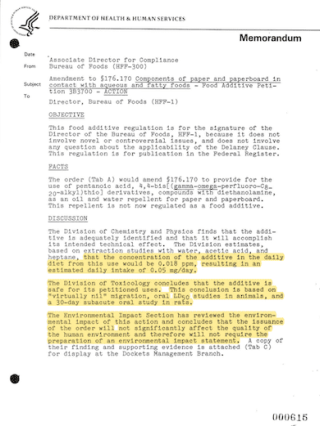

February 10, 1983

FDA evaluates a Ciba-Geigy petition filed at the end of 1982 to use a PFAS polymer in food packaging for various foods. FDA asks for additional information about migration testing.

March 7, 1983

FDA finds that duration of Ciba-Geigy’s acute toxicity and 30-day experiments were too short to calculate a no-effect level, but the data “may be considered adequate” if dietary exposure from migration is less than 50,000 ppt.

August 2, 1983

FDA recommends approving the Ciba-Geigy type of PFAS based on an estimated concentration in the daily diet of 18,000 ppt.

August 17, 1983

FDA clarifies that the 18,000 ppt estimate for the Ciba-Geigy PFAS in the daily diet applies only to use with fatty foods at room temperature. If approved for both fatty hot foods and fatty room temperature foods, the estimated concentration in the daily diet would be 67,000 ppt.

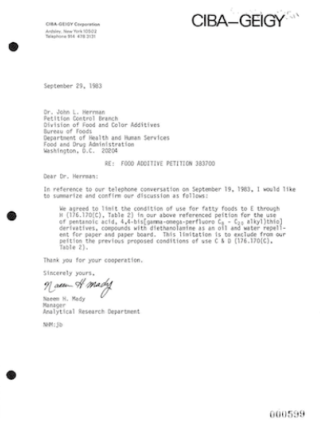

September 29, 1983

Ciba-Geigy writes to FDA agreeing to limit use to fatty room temperature foods.

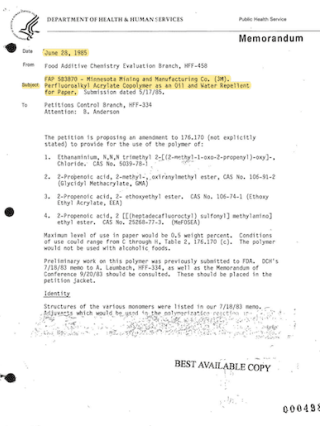

June 28, 1985

FDA evaluates a 3M petition for a new PFAS polymer to replace its previously approved PFAS polymer. FDA says the petition is not acceptable because 3M has not included enough chemical identity and migration testing information.

October 2, 1985

FDA recommends approving 3M’s new PFAS polymer. FDA estimates that each of the four main chemicals that make up the PFAS polymer will be in the daily diet at concentrations no higher than 10,000 ppt.

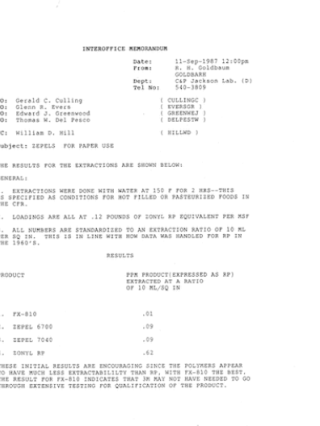

September 11, 1987

As part of the indirect food additive petition for Zonyl RP, DuPont told the agency it expected a migration rate of only 200,000 ppt. But an internal DuPont memo shows that Zonyl RP could contaminate food at 620,000 ppt.

November 5, 1993

FDA reviews a petition for a new Ciba-Geigy PFAS polymer, Lodyne, for use in contact with multiple kinds of food and concludes additional migration data is needed.

March 15, 1994

FDA finds that Ciba-Geigy has not adequately tested for gene effects from Lodyne. Based on migration data received, FDA recommends approval for use in containers for reheatable frozen or refrigerated foods but not for other uses without more data.

August 3, 1995

FDA approves Lodyne for use in containers for reheatable frozen or refrigerated foods.

August 30, 1996

FDA evaluates a Ciba-Geigy request to allow use of Lodyne in food packaging for five more categories of food. FDA estimates that as much as 520,000 ppt of Lodyne could migrate into food.

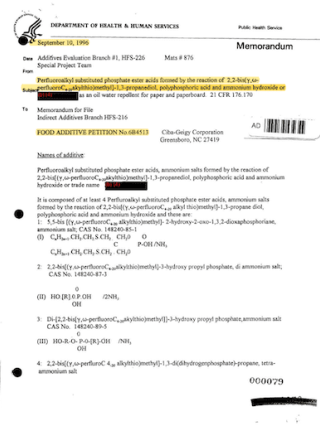

September 10, 1996

DOWNLOAD DOCUMENT2000-2020

FDA allows the use or expanded use of dozens of new PFAS formulas in food packaging.

August 1, 2000

FDA allows use of a new type of Ciba Specialty Chemicals PFAS, PFASCA, with an estimate that as much as 580,000 ppt could migrate into food, with as much as 11,000 ppt in the daily diet.

August 29, 2002

FDA reviews a two-year study of the oral toxicity of PFOA in rats and finds there are adverse effects to the liver and testis.

October 1, 2002

FDA estimates human cancer risk from exposure to PFOA as part of a review of a food contact notification from Dyneon.

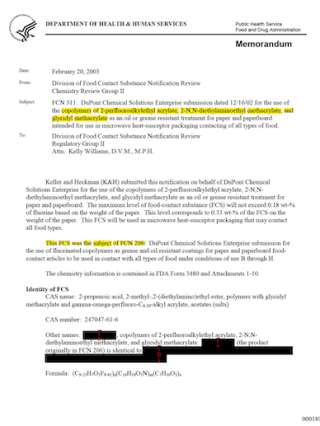

February 3, 2003

FDA accepts a DuPont food contact notification to expand uses of a DuPont PFAS to be applied to single-use microwave packaging and packaging for various kinds of food.

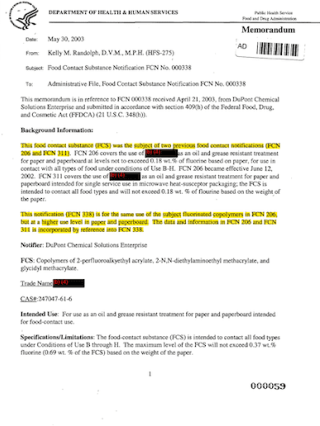

May 30, 2003

FDA accepts a DuPont request to increase the amount of its PFAS that can be used on paper and paperboard food packaging. DuPont says the new amount is “slightly higher,” but FDA finds use and dietary exposure are “essentially doubled.” DuPont does not provide any new data.

2005

FDA researchers publish an article showing PFAS migration into food from packaging and cookware.

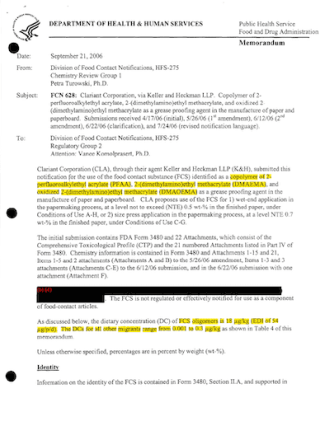

September 21, 2006

FDA reviews use of a new PFAS polymer by Clariant. FDA estimates that 21.275 μg/kg of two PFAS components of the polymer will migrate to food.

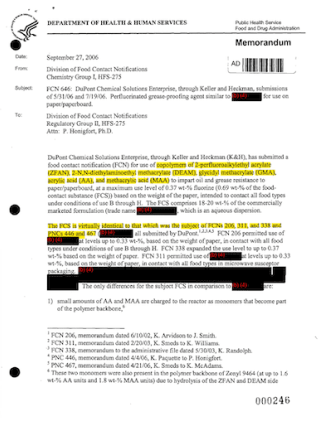

September 27, 2006

FDA reviews a DuPont request to use an updated formula of its PFAS polymer in food packaging. FDA rejects DuPont’s exposure calculations but allows the new formula because it estimates overall exposure to this formula to be lower than the previous formula.

October 29, 2006

As part of its review of the Clariant PFAS polymer, FDA analyzes a DuPont study of how much PFOE-acrylate builds up in the body. DuPont’s animal study shows the half-life is at least 21 days and could be as much as 100 days.

March 4, 2008

FDA researchers publish an article showing significant PFAS migration into food from popcorn and other foods. FDA also finds common migration testing methods may underestimate actual migration and that oils with emulsifiers can significantly increase the amount of PFAS that migrate to food.

September 30, 2010

FDA toxicologists finally raise concerns about the safety of long-chain PFAS used in food packaging.

March 20, 2013

FDA researchers publish another article studying migration of seven different long-chain PFAS into food from packaging.

October 17, 2014

Several NGOs, including EWG, petition the FDA to revoke approval for three long-chain PFAS chemicals approved for use in food packaging between 1967 and 1997.

January 28, 2015

An FDA researcher publishes an article on the potential toxicity of short-chain PFAS and the need to address data gaps.

January 4, 2016

FDA grants the NGO petition and revokes approval of three long-chain PFAS due to safety concerns.

February 2018

FDA researchers publish an article finding that breakdown products of 6:2 FTOH, a mixture containing PFAS commonly used in food packaging, could build up in the body for long periods.

February 2020

FDA researchers publish a new article on breakdown products of 6:2 FTOH and find that one of the breakdown products accumulated in the fat, liver and plasma of laboratory rats for over a year.

April 2020

FDA researchers publish another article that finds industry claims about the safety of 6:2 FTOH have largely ignored publicly available information and that the compound is more toxic than industry indicated to FDA.

July 30, 2020

FDA announces a voluntary phase-out of some short-chain PFAS, including 6:2 FTOH in food packaging. The voluntary phase-out gives industry until summer 2025 to get 6:2 FTOH off the shelves.